Formal Verification of the Aztec Governance Protocol

Authors: Thomas Pani, Igor Konnov

Date: December 9, 2025

1. Introduction

In August 2025, Aztec Labs engaged Thomas Pani and Igor Konnov to formally specify and verify the new Aztec Governance Protocol – the core on-chain system that governs Aztec Network.

Over the course of five weeks, we reviewed every line of code in scope and developed a precise formal specification, verified automatically with Apalache. The result: scalable, massively parallel automated verification that explored the entire protocol state space to formally confirm correctness and uncover subtle, cross-contract issues that conventional audits or fuzzing can easily miss.

The team at Aztec Labs reviewed our findings and addressed all of them.

At-a-Glance Metrics

For the impatient reader, here are some key figures:

| 125 invariants specified across 10 contracts, 8 libraries, and 8 interfaces |

| 992 verification conditions checked in total |

| 72 physical cores / 368 GiB RAM, running for 321 CPU-days (≈ 2 weeks) |

| Findings: 5 Medium • 3 Low • 6 Info (jump ahead) |

| Final complete verification run in 576 CPU-hours (≈ 1 calendar day) |

| Contract size: ~2 kLOC Solidity |

| Specification size: ~4 kLOC Quint (incl. traceability comments) |

These runtimes are comparable to large-scale fuzzing campaigns – but with a crucial difference: formal verification explores every possible transaction symbolically, offering exhaustive reasoning rather than probabilistic coverage.

Highlights

Some of the key highlights from this article include:

- Representative issue: Governance Insolvency with root-cause analysis and fix (§9.1)

- Choosing the right tools (§4)

- Bootstrapping the formal specification with AI (§5.2)

- Making verification scale with compositional reasoning and inductive invariants (§5.3, §7.3)

- Showing that the protocol can progress: witnesses of liveness (§7.4)

Our formal report can be accessed via this link and the specifications can be found via this link.

2. Overview of Aztec Governance

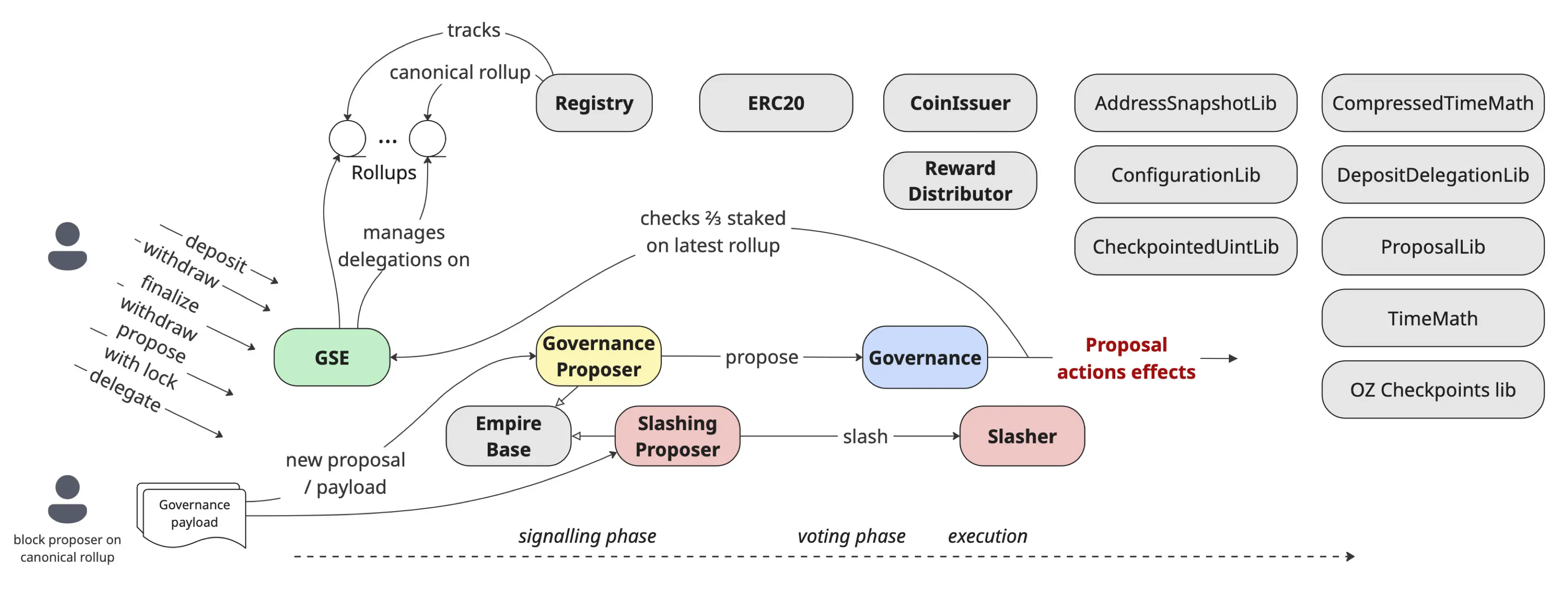

Aztec Network’s governance is implemented as a suite of on-chain Solidity contracts. We summarize its multi-contract architecture, which required compositional analysis to verify, in the diagram below. The current implementation extends and formalizes the concepts from the Aztec Governance RFC – see Aztec Governance for the canonical documentation. This post reflects the protocol as of the commit used in our engagement. Parts of the codebase have evolved since our engagement.

(We highlight the key contracts, with no special meaning attached to the colors.)

Rollups and Registry. Aztec Network manages a system of rollups recorded in the Registry, which directs inflationary rewards to a single, designated canonical rollup.

GovernanceProposer. GovernanceProposer (derived from EmpireBase) forms the foundational layer of the voting system, implementing a round-based signaling mechanism to determine which proposals advance to Governance.

Governance. The Governance contract manages the full proposal lifecycle, including submission, voting, and execution. Given their critical role in managing the Aztec Network, Governance incorporates access control, such as whitelisting beneficiaries that participate in voting. On top of that, it implements an emergency proposal mechanism which requires a substantial token lock.

Governance Staking Escrow (GSE). Governance stakes and corresponding voting rights are managed by the Governance Staking Escrow (GSE) contract. GSE enables seamless migration of staked assets to new canonical chains, addressing the “cold-start” problem by ensuring immediate operational support during network upgrades. Proposals made through GovernanceProposer tie back to GSE during execution, verifying that at least two-thirds of the total stake is allocated to the latest rollup.

SlashingProposer and Slasher. The SlashingProposer contract, also derived from EmpireBase, uses the same round-based signaling mechanism to determine which slashing proposals are forwarded to the Slasher contract.

Libraries. The main contracts are supported by a set of custom libraries that use storage-layout compression for gas optimization. These libraries enable the system to retrieve historical, checkpointed state for computing voting power, implement a custom checkpointed set data structure built on OpenZeppelin’s Checkpoints.Trace224 library, implement the vote-tallying algorithm, and provide helper functions that encode the proposal lifecycle state machine.

3. Attack Surface

The attack surface of the Governance Protocol is significant – with over 40 external state-mutating functions across multiple contracts in scope. Moreover, problematic scenarios typically:

- involve multiple contracts,

- exercise them over several transactions, and

- can even involve multiple instances of the same contract (e.g., several Rollups, several Governance contracts, etc.).

Reasoning about time. Governance and GovernanceProposer use the block timestamp to organize signaling and voting phases. GovernanceProposer slots are short (fractions of a minute), while Governance voting periods are much longer (minutes to days). We must therefore reason about long time horizons interrupted by short-lived events.

Malicious external inputs. To make things harder, we also considered scenarios in which a canonical rollup produces erroneous readings from time to time, e.g., due to a fault. For example, what if a canonical rollup starts to return slot numbers from the past (or far in the future)?

This poses both a challenge and an opportunity: standard techniques such as fuzzing, random simulation, or bounded model checking would not get us far – the state and action spaces are prohibitively large.

4. Choosing the Right Tools

With the attack surface in view, the next question was tooling: how to verify the protocol logic without drowning in bytecode.

4.1. Protocol-Level Specification

From an engineer’s perspective, the ideal solution would be to verify correctness directly at the implementation level – that is, to automatically reason about the Solidity code itself. Tools such as Certora Prover, Kontrol, Halmos, and HEVM aim to do exactly this by automating formal reasoning over smart contracts. These tools are remarkable engineering achievements, but their task is inherently complex: among other things, they must reason precisely about stack behavior, memory, storage, and external calls – all the way down to the EVM bytecode.

Before diving into such low-level reasoning, however, we believe it is essential to ensure that the protocol’s logic is sound. If high-level properties of the protocol are violated, then verifying bit-level correctness provides limited value. Once the protocol logic is verified, attention can shift to the implementation.

In this project, we focused on specifying the Aztec Governance Protocol at the logic level. Our main objectives were to:

- specify the high-level behavior of the protocol,

- identify its core invariants, and

- prove these invariants correct (or demonstrate violations through counterexamples).

4.2. Languages and Tools

Several specification languages could serve this purpose. For instance, we could have expressed the protocol directly in an interactive theorem prover like Lean or Rocq. However, both would offer little automation, which would make limited progress feasible within our one-month timeframe. (Recently, Lean has seen exciting developments such as the grind tactic and research by the VERSE group. We may explore these in a future engagement!)

TLA+ and its tooling. TLA+ is perhaps the most well-known practical specification language. It is supported by two model checkers (TLC and Apalache) and an interactive theorem prover TLAPS. We use the methodology of TLA+ to reason about the Governance Protocol as a collection of interacting state machines over large state spaces. Since many engineers find the syntax of TLA+ confusing, we use the surface syntax Quint to write the specifications. As co-authors of both Quint and the Apalache model checker – together with Gabriela Moreira, Shon Feder, Jure Kukovec, and others – we have a deep understanding of their internals and how to apply them to large-scale protocol verification. This expertise was essential for scaling our analysis to a system as complex as Aztec Governance.

5. Specification Decisions and Challenges

With the goals and tools defined, the next step was to translate the Governance Protocol into a precise, analyzable specification.

5.1. Writing the Specification

Modeling the states. Before specifying the contract behavior, we must decide how to model the contract states. We first define the shape of individual contract states. For example, below is the state of a GovernanceProposer.

// GovernanceProposer contract state

type GovernanceProposerState = {

// the state of the parent EmpireBase contract

empireBase: EmpireBaseState,

// mapping(uint256 proposalId => address proposer)

proposalProposer: Uint256 -> Address,

// immutable config (set in constructor)

REGISTRY: Address,

GSE: Address

}

You can see that many concepts from Solidity (like mappings) are seamlessly expressed in Quint. The full protocol state – including all relevant contracts – is captured by EvmState. In our case, an EVM state is structured as follows:

type EvmState = {

block_timestamp: Uint256,

// all possible instances of ERC20 used as assets

assets: Address -> ERC20State,

// all possible instances of Governance

governances: Address -> GovernanceState,

// all possible instances of GovernanceProposer

governanceProposers: Address -> GovernanceProposerState,

// all possible instances of GSE

gses: Address -> GSEState,

// all possible instances of Registry

registries: Address -> RegistryState,

// all possible instances of RewardDistributor

rewardDistributors: Address -> RewardDistributorState,

// all instances of Slasher

slashers: Address -> SlasherState,

// all instances of SlashingProposer

slashingProposers: Address -> SlashingProposerState,

// IEmperor(...).getCurrentSlot() for each rollup

rollupSlot: IHaveVersion -> int,

// IEmperor(...).getCurrentProposer() for each rollup

rollupProposer: IHaveVersion -> Address,

// mapping rollup addresses to their versions

// Corresponds to _rollup.getVersion() call in Registry.sol:53

ROLLUP_VERSIONS: IHaveVersion -> Uint256,

// mapping rollup address to the reward distributors that they create

REGISTRY_REWARD_DISTRIBUTORS: IHaveVersion -> IRewardDistributor

}

As you can see, we do not have to focus on nitty-gritty low-level details – like how storage is laid out in EVM. This frees us to focus on protocol logic and high-level correctness, rather than low-level implementation concerns. It also makes the reasoning problem more tractable for automated verification.

Modeling the contract functions. The contract functions are simply pure functions over the EVM state. For instance, we define the function initiateWithdraw in Quint as:

// Governance.sol#L341

pure def Governance::initiateWithdraw(__evm_state: EvmState,

__self: IGovernance, __msg_sender: Address,

_to: Address, _amount: Uint256): Result[EvmState] = {

val __state = __evm_state.governances.get(__self)

val config = __state.configuration

// ConfigurationLib.sol#L36:

// Timestamp.wrap(Timestamp.unwrap(_self.votingDelay) / 5) +

// _self.votingDuration + _self.executionDelay;

val withdrawDelay = config.votingDelay / 5

+ config.votingDuration + config.executionDelay

// L342: _initiateWithdraw(msg.sender, _to, _amount,

// configuration.withdrawalDelay());

Governance::_initiateWithdraw(__evm_state, __self, __msg_sender,

_to, _amount, withdrawDelay)

}

In Quint, we explicitly model all side-effects of the Solidity code, including exceptions and reverts. While it makes our specification more verbose, all branches and assignments become immediately visible at the code level – auditors do this in their heads all the time. For example, _initiateWithdraw computes and returns an updated EvmState, unless it reverts:

// Governance.sol#L694

pure def Governance::_initiateWithdraw(__evm_state: EvmState,

__self: IGovernance, _from: Address, _to: Address,

_amount: Uint256, _delay: Timestamp): Result[EvmState] = {

val __state = __evm_state.governances.get(__self)

// L695: users[_from].sub(_amount);

val fromAmount = __state.users.getOrElse(_from, checkpoints::constructor)

val userTraceOrError = checkpoints::sub(__evm_state, fromAmount, _amount)

if (isErr(userTraceOrError)) {

err(__evm_state, userTraceOrError.err)

} else {

// L696: total.sub(_amount);

val totalTraceOrError = checkpoints::sub(__evm_state, __state.total, _amount)

if (isErr(totalTraceOrError)) {

err(__evm_state, totalTraceOrError.err)

} else {

// L698: uint256 withdrawalId = withdrawalCount++;

// L700: withdrawals[withdrawalId] = Withdrawal({...});

val withdrawal = {

amount: _amount,

unlocksAt: __evm_state.block_timestamp + _delay,

recipient: _to, claimed: false

}

val __state1 = {

...__state,

users: __state.users.put(_from, userTraceOrError.v), // L695

total: totalTraceOrError.v, // L696

withdrawals: __state.withdrawals.append(withdrawal), // L700

}

ok({...__evm_state,

governances: __evm_state.governances.put(__self, __state1)

})

}

}

}

Modeling transactions. We model transactions, e.g., initiated by externally-owned accounts (EOAs), via Quint actions:

action governance_initiate_withdraw = {

nondet _g = evm.governances.keys().oneOf()

nondet _sender = ALL_SENDERS.oneOf()

nondet _to = ALL_ADDRESSES.oneOf()

nondet _amount = 0.to(MAX_UINT256).oneOf()

val result = Governance::initiateWithdraw(evm, _g, _sender, _to, _amount)

all {

is_valid_sender(_sender) and isOk(result),

evm' = result.v,

// ...

}

}

This directly controls the domains from which input parameters are drawn. When we run the Quint randomized simulator, non-deterministic values are sampled uniformly at random. When we run the Apalache model checker, it uses logic constraints in the Z3 SMT solver to reason about all possible non-deterministic values at once.

5.2. Bootstrapping the Formal Specification with AI

The above specification looks a bit machine-generated. This is not far from the truth. We used an LLM to produce the initial specifications, given the source code in Solidity and the Quint data types.

Obviously, an LLM cannot make high-level modeling decisions, like how to structure the EVM state, or how best to turn Solidity into functional definitions – this requires years of practical experience. We developed a custom system prompt that gives the LLM clear instructions and examples for translating Solidity into Quint. (It’s an internal tool we refine and apply with clients when we bootstrap their specifications.)

Of course, as with all AI assistants, we had to carefully proofread the translation results. Also, we were fortunate to have the model checker Apalache on our side – it automatically pointed us to some inconsistencies in the translation. Compared to writing the specification by hand, this approach allowed us to bootstrap the project very quickly and to start evaluating the protocol early on.

5.3. Compositional Reasoning

Some security researchers believe that formal verification does not scale to more than 1–2 smart contracts, or to exploit scenarios longer than 1–2 external calls deep. We have organized our specification in such a way that the verification tools can deal with the behavior of 10–20 smart contracts, and arbitrarily long transaction sequences. This level of scalability requires not just formal verification expertise, but a deep understanding of how model checkers and provers work internally and interact with protocol architecture. It builds directly on our prior formal verification work – including zkSync Governance, ChonkyBFT, and Ethereum 3-slot-finality – where we pushed verification tools to reason compositionally across complex systems. More on this in Section 7.3. Inductive Invariants: Making Verification Scale.

6. Protocol Invariants

From Aztec’s documentation and source code, we extracted and formalized 125 key invariants of the Governance Protocol. To get a taste of the invariants, here are a few examples in English (more of them are in the report):

- GOV-16: If the proposal has not been active yet, then no votes have been cast.

- GOV-20: The timestamps in the

userstraces are ordered. - GOV-26: For each timestamp

t,total[t]equals the sum of the users’ voting power att. - GP-02-01: For each submitted proposal in

proposalProposer, there is round accounting for a corresponding executed proposal (i.e., submitted to Governance). - GP-08: A proposal cannot be executed without a quorum.

- GSE-17: for each proposal that the

delegateehaspowerUsedon, Governance contains that proposal. - GSE-19:

powerUsedcannot exceed the attester’s voting power at the time of the proposal’spendingThrough. - GSE-23:

delegation.supplyat each checkpoint is the sum of alldelegation.ledgers[instance].supplyat that time. - SP-10: lastSignalSlot is in the valid range.

This range is

[round * ROUND_SIZE, (round + 1) * ROUND_SIZE). - SP-11: The number of signals is correct. It does not exceed

lastSignalSlot % ROUND_SIZE + 1.

Formalized invariants in Quint. We formalized all 125 invariants in Quint as

well. For example, the Governance contract should uphold the Solvency Invariant

(‘The Holy Grail’, as coined by FV researchers at

Certora):

// GOV-28: Solvency: Governance holds enough balance to cover all future

// withdrawals.

pure def governance_solvency_inv(_evm: EvmState, ga: IGovernance): bool = {

pure val g = _evm.governances.get(ga)

and {

// the withdrawals that happen in the future

pure val payable = g.withdrawals.indices().fold(0, (sum, i) => {

pure val withdrawal = g.withdrawals[i]

sum + if (withdrawal.claimed) 0 else withdrawal.amount

})

// the total user's balance, add payable, is below the contract's balance

pure val asset = _evm.assets.get(g.ASSET)

g.total.latest() + payable <= asset.balances.getOrElse(ga, 0)

}

}

Turns out, the solvency invariant is actually violated under certain conditions. We will get back to it in Section 9.1. Governance Insolvency.

With the key invariants defined, we started verifying them using Quint and Apalache.

7. Formal Verification Workflow

As soon as parts of the specification stabilized, we began verification – moving from randomized simulation to full symbolic and inductive reasoning.

7.1. Randomized Simulator: Stuck at Unproductive Inputs

The Quint randomized simulator operates similarly to property-based testing for implementation languages: it assigns concrete values to nondet declarations and resolves non-deterministic control choices by selecting one branch at random.

Limitations. We briefly experimented with this approach, but it proved ineffective for our purposes. The simulator’s uniform random sampling consistently failed to produce valid configurations that would even satisfy the protocol’s initial state:

$ quint run --max-samples=100000 --max-steps=10 --invariant=past_signals \

spec/slashing_proposer_machine.qnt

An example execution:

[ok] No violation found (768ms at 130208 traces/second).

Trace length statistics: max=0, min=0, average=0.00

We believe the randomized simulator could be improved in future versions. If you’d like to explore in more detail why this happens – and how it could be mitigated – check out our workshop 25-Minute Solidity Fuzzer: Fuzzing Smarter, Not Harder.

In its current form, however, it did not help us uncover issues. This led us to use the symbolic analysis tools in Apalache, which can reason over all possible inputs symbolically rather than sampling concrete ones.

7.2. Symbolic Random Walks: Scaling Up

With symbolic random walks (part of Apalache), we quickly checked several invariants. The following run revealed an issue: the system could receive outdated (“past”) signals when the canonical rollup was faulty:

$ quint verify --random-transitions=true --max-steps=10 \

--invariant=past_signals spec/slashing_proposer_machine.qnt

...

[violation] Found an issue (22181ms)

When an invariant is violated, Apalache produces a counterexample with all details needed to understand the issue. We omit it here because it is quite verbose.

Limitations. Even though this approach proved to be quite useful in bootstrapping and debugging our specification, it reached its limits when we began dealing with multiple contracts. This limitation stems from the protocol’s scale – with over 40 external functions, many of which can be invoked at nearly any point in time, the number of possible symbolic paths grows combinatorially with path length. We then moved to proving inductive invariants automatically.

7.3. Inductive Invariants: Making Verification Scale

To scale our formal verification efforts further, we specified 125 invariants that together capture any arbitrary state of the Governance Protocol. For example, below is the invariant gse_rollups_inv that groups the invariants GSE-28 to GSE-32:

pure def gse_rollups_inv(evm: EvmState, gsea: IGSE): bool = {

val gse = evm.gses.get(gsea)

val chkpts = gse.rollups._checkpoints

and {

// GSE-28: `rollups` is an ordered checkpointed trace with ascending timestamps

_trace_is_ordered(gse.rollups),

chkpts.indices().forall(i => and {

// GSE-29: `rollups` values are rollup addresses

chkpts[i]._value.in(ROLLUP_ADDRESSES),

// GSE-30: the bonus instance does not appear in the `rollups` history

chkpts[i]._value != BONUS_INSTANCE_ADDRESS,

// GSE-31: `rollups` values are registered in `instances`

chkpts[i]._value.in(gse.instances.keys()),

})

}

}

The following command checks that all protocol invariants (all_inv) – including gse_rollups_inv – hold whenever the protocol is in a state that satisfies all_inv and one of the contracts makes a single step:

$ ./scripts/quint-inductive.sh spec/invariant_model.qnt 31 32 5 100 all_inv

Beware that the above command runs over 900 verification runs in parallel (in the example above using at most 5 CPUs at once). This can easily overwhelm your laptop. If you want to reproduce our experiments, read the next section on our experimental setup.

Scalable verification. The core technique that enables this level of scalability is the use of inductive invariants. Instead of exploring all possible symbolic paths of the specification from an initial state (this approach, used by most code-level symbolic tools, is called symbolic execution), we start with a much richer set of states (captured by the inductive invariant all_inv) and simply enumerate all possible external functions and make them execute exactly once from any state in the inductive invariant. By assuming that all_inv holds in an arbitrary state and showing that it still holds after symbolically executing any single transaction, our check extends inductively to all possible executions.

Note for sticklers. We still have to show that the initial states satisfy the inductive invariant. In our case, this is easy. Essentially, the initial state of the protocol is an “empty” EVM state where none of the governance contracts are deployed yet.

7.4. Witnesses of Liveness: Proving the Protocol Can Progress

When verifying safety, there is always a risk that we introduce a bug in the specification that restricts the protocol behavior too much. This would still keep the protocol “safe” from the verification point of view, but, obviously, the protocol would not do as many useful things as it is meant to do. To avoid this pitfall, we introduce “falsy invariants” that instruct Apalache to generate a witness of the protocol reaching an “interesting” state. Below is an example to produce an execution to a state in which at least one governance proposal has been executed:

// Check this invariant to find an example of having at least one executed proposal:

// quint verify --max-steps=0 --invariant=gov_proposals_executed_ex \

// spec/invariant_model.qnt

val gov_proposals_executed_ex = {

not(evm.governances.keys().forall(ga => {

val g = evm.governances.get(ga)

g.proposals.indices().exists(proposalId => {

val proposal = g.proposals[proposalId]

proposal.cachedState == ProposalState_Executed

})

}))

}

This ability to automatically generate an execution trace to an ‘interesting’ state is a superpower of symbolic model checkers like Apalache – a functionality that would be far more difficult to automate with an interactive theorem prover such as Lean or Rocq. (Provers have property-based testing tools, but they are not tuned to bug finding in distributed protocols like Apalache.)

8. Experimental Setup and Verification Runs

Experimental setup. As mentioned above, checking the inductive invariant of our specification produces 992 verification tasks in total (for the combinations of a specific invariant and an external function call). Apalache decomposes invariant checking into smaller tasks, so we employ GNU parallel to massively parallelize the verification. We use two servers to run the experiments:

- AMD Ryzen 9 5950X processor (16 physical, 32 logical cores), 128 GB memory

- 2× Intel Xeon Platinum 8280 processor (56 physical, 112 logical cores total), pinned at 3.1 GHz, 240 GB memory

Verification Runs. Some of the verification tasks take a few minutes to check, and some of them take a few hours. This is caused by the nature of the SMT constraints. It is well-known that SMT solvers, including Z3, are challenged by non-linear integer arithmetic – in this project, they naturally appear, e.g., as part of Aztec’s vote tallying logic.

Instead of writing many words, we simply show you the plot below. It visualizes the running times of Apalache when checking the 992 verification tasks. The X-axis shows the number of verification conditions solved (roughly, individual constraints in the inductive invariant), sorted from fastest to slowest. Each point corresponds to one verification condition. The Y-axis represents the running time per verification condition, formatted in human-readable units (milliseconds to hours). Notice the logarithmic scale!

As we can see from the plot, over 85% of the verification conditions are checked in less than 10 minutes each, about 7% are checked in several hours, and about 8% of the verification conditions require plenty of running time.

Timeouts. As it happens with SMT solvers, 3% of our verification conditions time out. These are the runs at the end of the “hockey stick”. We capped the running time of Z3 at 12 hours. Since we are decomposing the inductive invariant into smaller pieces, these problematic conditions are well-localized. We have investigated these conditions. They all have to do with non-linear arithmetic.

Below is an example of such an invariant. Notice that the very last expression involves modulo over a non-constant value, since ROUND_SIZE is initialized in the contract constructor.

// GovernanceProposer invariant on last signals and total signals

pure def governance_proposer_signal_inv(evm: EvmState,

ga: IGovernanceProposer): bool = {

val gp = evm.governanceProposers.get(ga)

gp.empireBase.rounds.keys().forall(rollup => {

gp.empireBase.rounds.get(rollup).keys().forall(round => {

val rollupRounds = gp.empireBase.rounds.get(rollup)

val accounting = rollupRounds.get(round)

and {

// GP-12: ...

// ...

// GP-13: The number of signals is in the right range

// It does not exceed `lastSignalSlot % ROUND_SIZE + 1`.

// This property is very hard for Z3. It is not falsified.

and {

gp.empireBase.ROUND_SIZE <= MAX_ROUND_SIZE,

totalSignalCount >= 0,

totalSignalCount <= gp.empireBase.ROUND_SIZE,

totalSignalCount <=

(accounting.lastSignalSlot % gp.empireBase.ROUND_SIZE) + 1,

}

}

})

})

}

We classify the small number of the verification conditions that time out as not falsified rather than verified. Usually, we recommend verifying such conditions with a theorem prover such as Lean or Rocq. Another solution is to fix these non-constant values to known production configuration values to gain further confidence.

9. Findings

Our verification of the Aztec Governance Protocol uncovered five Medium, three Low, and six Informational findings. Most arose from subtle cross-contract interactions that are difficult to identify through conventional testing, fuzzing, or simulation alone. We reported all issues to Aztec Labs, who acknowledged and/or fixed them in subsequent pull requests.

Below we explain one representative issue: a violation of the solvency invariant.

9.1. Governance Insolvency

Recall the solvency invariant from Protocol Invariants. When we check it, Apalache produces a counterexample. Below is the root cause of this issue:

function deposit(address _beneficiary, uint256 _amount) external

override(IGovernance) isDepositAllowed(_beneficiary) {

ASSET.safeTransferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), _amount);

// <--- if msg.sender == address(this), then the balances do not change

users[_beneficiary].add(_amount);

// <--- ...but the liabilities always get increased

total.add(_amount);

emit Deposit(msg.sender, _beneficiary, _amount);

}

In short, executing an approved governance proposal can invoke Governance.deposit(...). Inside deposit, this performs an ERC-20 self-transfer – leaving token balances unchanged – while crediting _beneficiary and increasing total. Governance’s liabilities go up, but its assets don’t – the contract becomes insolvent. The diagram below illustrates the problematic scenario.

On ERC-20 approvals. Most ERC20 token implementations would require Governance to execute an explicit token approval for the self-transfer before the call to deposit() (while executing the governance proposal). Calling ASSET is forbidden by the current Governance implementation. However, certain tokens like WETH do not require approvals for transferFrom() if from == msg.sender.

Resolution. We raised this finding with Aztec Labs who addressed it in PR #16917 by forbidding Governance from calling deposit() itself. In addition, the current AZTEC token implementation uses OpenZeppelin’s ERC-20 implementation, which does require explicit approval of self-transfers.

9.2. Other Findings

For details on all our findings, refer to our formal report.

10. Conclusion: Scalable Formal Verification in Practice

Our formal verification of the Aztec Governance Protocol went far beyond a traditional audit. It was a compositional, protocol-level analysis using state-of-the-art tools and techniques that we helped create. We formally proved 125 high-level invariants across a multi-contract system – reasoning over a search space beyond the reach of traditional testing and most formal verification tools. These invariants were automatically decomposed into 992 verification conditions, which let us further parallelize the verification task.

By combining inductive invariants, symbolic reasoning, and massive parallelization (321 CPU-days of compute), we showed that formal verification can scale to the complexity of modern, mission-critical smart contract systems. Our methodology enables exhaustive, automated reasoning about real-world governance mechanisms and other smart contract protocols.

For systems like Aztec Governance, where bugs are subtle but potentially catastrophic, deep understanding of the tools and underlying logic is essential. This project demonstrates that scalable, unbounded formal verification is not just theoretically possible – it’s practical today for mature, production-grade protocols.

Differential Testing: Spec / Implementation Conformance

A natural next step would be to connect the formal protocol specification with the actual Solidity implementation to close the verification loop (known as differential or conformance testing). With our methodology, it suffices to check that each external function call in Solidity conforms to its formal specification in Quint. Traditionally, this is done by writing and proving pre- and post-conditions in Hoare logic – e.g., using Certora Prover. We suggest that a more pragmatic approach is to fuzz external Solidity functions directly against the formal specification.

Enabling diff testing in Apalache: We have just implemented a new Apalache JSON-RPC API, which enables interactive differential testing between implementation and specification. This delivers fast, actionable, and reproducible results while still providing a high level of assurance grounded in rigorous formal modelling.

If you want to pick up my brain for a few hours, drop me an email. After that, we can switch to a messenger of your choice (e.g., Signal, Telegram, or others) or have a call. For short consultations, I accept payments via Stripe. I also consider longer-term engagements (from weeks to months), which would require a contract. You can see my portfolio at konnov.phd. I am based in Austria (CET/CEST) and have experience working with clients from the US, UK, and EU.

The comments below are powered by GitHub discussions via Giscus. To leave a comment, either authorize Giscus, or leave a comment in the GitHub discussions directly.