Specification and model checking of BFT consensus by Matter Labs

Or model checking fault-tolerant algorithms that have more states than the atoms in the universe

Author: Igor Konnov. Joint work with MatterLabs (Bruno França, Denis Firsov, Denis Kolegov, Grzegorz Prusak)

Update: We have published an arXiv paper about ChonkyBFT. Check the details here.

1. Introduction

Earlier this year, I was engaged by the Security Team at MatterLabs. They needed help in formally specifying and checking the properties of the new algorithm that was being designed by the Consensus Team. What intrigued me is that the Consensus Team had the experience of implementing BFT algorithms with their Era Consensus, but their new algorithm – called ChonkyBFT – existed only in Rust-like pseudo-code. So the team wanted to start with a formal specification before diving into a full-featured implementation. Since I had the experience in specification and model checking of the Tendermint consensus at Informal Systems, this seemed like a feasible task to me.

This blog post summarizes the work done so far as well as the experience of using pragmatic verification tools in a cutting-edge blockchain company. We have checked a number of properties with Quint and Apalache. This is still a work in progress, as we are constructing an inductive invariant, which would give us even better safety guarantees than we have obtained so far.

If you want to skip the details and jump to the conclusions, here are the most important outcomes of this work, in my opinion:

-

We have written a formal specification of ChonkyBFT in Quint, which very closely follows the informal pseudo-code specification and fills the gaps of the pseudo-code.

-

Our specification is type-correct and executable. Basic tests against the specification are integrated into the CI on GitHub. Every time a change is made to the protocol specification, a number of test scenarios are run in the CI. You can play around with this specification instead of drawing diagrams on a whiteboard.

-

We have conducted model checking experiments. These experiments have uncovered relatively small inconsistencies in the informal specification as well as a few missing message validation tests, which would let the faulty replicas fork the system. Moreover, the model checker was showing us breaking changes in a matter of several hours, whenever we refactored the protocol. While several hours may sound like a lot, it is a very fast feedback loop, compared to the manual protocol review.

-

In addition to that, we have adapted the Twins technique to Quint specifications.

-

We have discussed the assumptions of the core consensus protocol about the other protocols, for example, the interaction between the consensus protocol, the block fetcher protocol, and the gossip layer. As a result, some parts of the block fetcher were integrated into the core consensus protocol.

-

Due to the extremely large state space of the protocol, the model checker was demonstrating significant slowdown in the analysis of some transitions. We have identified a few problematic data structures. The Consensus team has optimized these data structures without breaking the invariants. Not only has this change visibly sped up the model checker, but it also decreased the size of the messages.

-

To further mitigate the slowdown, we guided the model checker to detect interesting examples faster, which can be done naturally in Quint.

-

In addition to confirming that the state invariants hold true, we have also produced counterexamples to the invariants, when the number of faulty replicas went over the expected threshold. This is a crucial step to demonstrate that our specification is not over-constrained.

Interestingly, this work reinforces the vision of Quint, which I presented at Gateway to Cosmos in 2023.

2. Choosing the specification language and tools

Before we started the specification efforts, we had to decide what specification language to use. Obviously, I had plenty of experience with TLA+ and Quint and all of the accompanying tools. Apart from impressive expertise in protocol design, engineering, and testing, the team at Matter Labs had previous experience with Alloy and Event-B. Basically, we had two points of view, both of them valid:

-

The researchers knew from their previous experience that fresh verification tools had a tendency to break in unexpected places. From that perspective, when using Quint we had a risk of writing half of the formal specification and then realizing that the tools were broken beyond repair. TLA+ tooling was much more mature and versatile.

-

The software engineers were saying that the Quint syntax looked much more approachable than the syntax of TLA+. Moreover, Quint was offering more familiar tools such as the randomized simulator and a testing framework.

As a result of this discussion, we arrived at the following compromise: We try Quint, and if its tooling breaks beyond repair, I would rewrite the specification in TLA+. Since the TLA+/Quint specifications rarely go over 2 KLOC, and both languages build upon the same logic of TLA+, it did not sound like a completely bizarre idea. In the end, we did not have to rewrite our specification in TLA+, though I had to work around several unimplemented features of Quint (more on this later). To our luck, back at Informal Systems, we had built more solid tooling for Quint than the typical minimal-viable-product approach required from us.

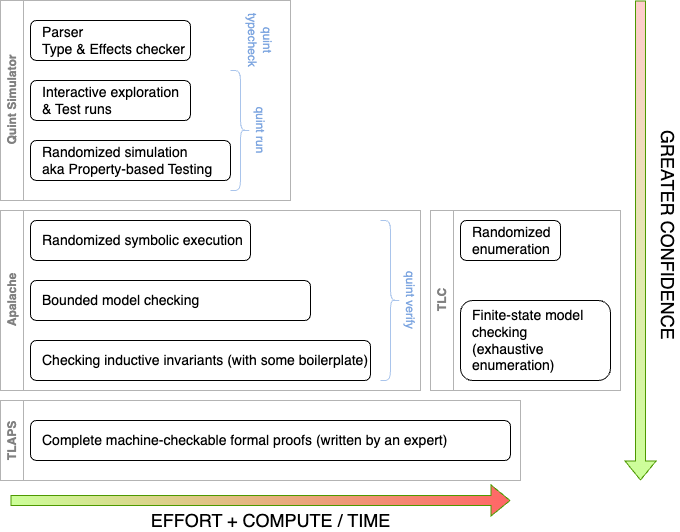

I will not go into details about the tooling offered by Quint and the TLA+ infrastructure. It would be a good topic for a separate blog post. Figure 1 captures the spectrum of the tools that are offered by Quint and the TLA+ ecosystem:

-

Quint offers a testing framework similar to property-based testing. It also has a randomized simulator that requires minimal expertise.

-

Apalache offers several approaches to symbolic execution and bounded model checking via SMT solvers (satisfiability-modulo-theory solvers).

-

TLC implements exhaustive state enumeration as well as randomized enumeration. (We have placed it to the right of Apalache in the figure, as TLC would require immense resources to check the protocol that we are investigating.)

-

TLAPS offers a proof system and a proof checker, also backed by SMT solvers.

In this work, we have used a subset of the available tools: Quint’s tests and its randomized simulator, Apalache’s randomized symbolic execution, and bounded model checking. We are currently investigating whether we would be able to leverage Apalache to show safety for unbounded executions by constructing inductive invariants. Since we were doing model checking, we were able to achieve greater degrees of confidence in the course of several weeks than we would be able to achieve with naive testing or randomized simulation. However, model checking is inherently incomplete in our setting, as it only proves or disproves properties for fixed parameters. To achieve complete verification, we would have to use a proof assistant such as TLAPS, Lean, or Coq, which would require a much greater project budget than is typically allocated for a security audit.

3. Distributed consensus in a nutshell

ChonkyBFT is a new Byzantine fault-tolerant protocol for distributed consensus. It blends together recent inventions in distributed computing, e.g., quorum certificates that can be traced back to HotStuff, the resilience condition of $n > 5f$ like in FaB. The protocol also includes the own discoveries by the Consensus Team.

In a nutshell, the BFT consensus works as follows. The distributed system is composed of n replicas, up to f of which may be Byzantine: The faulty replicas may simply crash, send messages to subsets of replicas, and send conflicting messages to subsets of replicas. Importantly, the Byzantine replicas can not forge the signatures of the $n - f$ correct replicas. To keep things simple, we assume that $n > 5f$. In the more realistic setting, each replica $n_i$ is assigned a weight $w_i$, and we assume that the sum of all weights is at least five times greater than the sum of the weights of the $f$ faulty replicas. Under these assumptions, the minimal interesting network configurations are as follows:

-

Six correct replicas: $n = 6, f = 0$. The algorithm should work correctly.

-

Five correct replicas and one faulty replica: $n = 6, f = 1$. The algorithm should tolerate one faulty replica.

-

Four correct replicas and two faulty replicas: $n = 6, f = 2$. The faulty replicas may break safety.

The goal of the replicas is to agree on the next block to commit onto a

blockchain. For specification purposes, the actual content of the blocks is

irrelevant. Hence, we assign some abstract values to blocks such as “val_0”,

“val_1”, or “inv_2”. As is common, most protocol operations are actually

done at the level of block hashes instead of complete blocks. The blocks are

involved only in a few cases, e.g., when a replica receives a proposal, or

when it receives a block from the gossip layer.

The correct replicas are progressing in views, starting with view 0. In every view, a replica may receive a proposal from the view proposer (programmatically known to all replicas), commit a block, issue a timeout, or switch to the next view, as soon as it has received a justification to do so (e.g., a timeout quorum certificate). When a replica receives a quorum of commit messages for a certain block — signed commit votes from $n - f$ replicas — it commits a block. In this case, the replica also sends the commit quorum certificate, so late replicas could catch up fast, instead of aggregating quorums of their own.

The algorithm contains a number of optimizations for converging fast in the “common case” when things go well, e.g., the network is responsive, and the proposer for the current view is not faulty. In addition to that, the protocol is optimized for the case of re-proposing the same block, when the replicas have received sufficiently many commits from a sub-quorum of $n - 3f$ replicas. To this end, each replica stores the summary of the other replica’s states that it has learned about by receiving messages, e.g., the high vote, the high commit quorum certificate, etc. The concrete fields can be seen in ReplicaState.

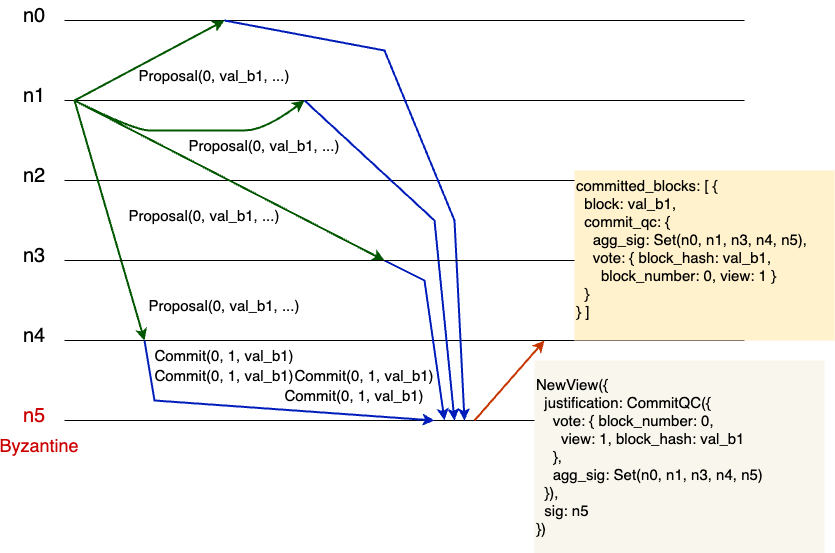

Figure 2 demonstrates a distributed computation of six replicas, with

replica n5 being faulty. Initially, replica n1 sends the proposal for the

block “val_b1” to be committed as the block number 0. The replicas $n_0$,

$n_1$, $n_2$, and $n_4$ receive this proposal and send their commit vote. The

faulty replica $n_5$ assembles the signed votes of $n_0$, $n_1$, $n_2$, and

$n_4$ and sends the new-view message that contains the signatures of $n_0$,

$n_1$, $n_2$, $n_4$, and $n_5$ itself. This is a perfectly valid message, as

$n_5$ could send a commit vote of its own. Finally, replica $n_4$ receives the

new-view messages, checks all the signatures, and commits the block “val_b1”,

since it has received a commit quorum certificate in the view message. This is

one of the shortest examples of just seven steps that were generated by the

model checker Apalache. The model checker produces output in Quint,

TLA+, and JSON. I drew the figure by hand, though one could automate

this process by parsing the JSON output.

If you want to see a concise description of the protocol, the best place to start is with the informal specification in rust-like pseudo-code. The description is actually quite concise, so the protocol may seem to be deceivingly simple. Once you start asking questions about certain parts of the protocol, it is probably a good time to switch to the formal specification in Quint.

In terms of formal specification, we were mostly interested in showing the safety of the protocol, that is, no disagreement on the blocks for the block number, as well as in finding examples that would demonstrate its liveness, that is, reaching a global state, where a correct replica commits one or more blocks.

4. Choice of abstractions

Abstracting cryptography. The Consensus Team has chosen a good level of abstraction when they were writing their informal specification. For instance, the focus was on the distributed aspects of the protocol, assuming that the cryptography primitives were working as expected. As real cryptography usually stands in the way of automated reasoning, we immediately introduced common abstractions: the hashes are perfect (actually, just the identity function), the public and private keys are just node identities, etc. These definitions can be found in types.qnt. For example:

// For specification purposes, a block is just an indivisible string.

// We can simply use names such as "v0", "v1", "v2". What matters here

// is that these names are unique.

type Block = str

// For specification purposes, we represent a hash of a string `s` as

// the string `s`. This representation is collision-free,

// and we interpret it as opaque.

type BlockHash = str

// Get the "hash" of a string

pure def hash(b: str): BlockHash = b

Tracking sent messages. Whereas an actual implementation of consensus would have to send and receive messages by sending and receiving them over the wire, our formal specification has the global view of the distributed system. Hence, we simply store the sent messages and access them, whenever needed. For example:

// the set of all Timeout messages sent in the past

var msgs_signed_timeout: Set[SignedTimeoutVote]

// the set of all SignedCommitVote messages sent in the past

var msgs_signed_commit: Set[SignedCommitVote]

// the set of all NewView messages sent in the past

var msgs_new_view: Set[NewView]

// the set of all Proposal messages sent in the past

var msgs_proposal: Set[Proposal]

// ...

action on_proposal(id: ReplicaId, proposal: Proposal): bool = all {

// [...]

// Send the commit vote to all replicas (including ourselves).

msgs_signed_commit' =

msgs_signed_commit.union(Set({ vote: vote, sig: sig_of_id(id) })),

// [...]

}

// ...

action replica_step_no_timeout(id: ReplicaId): bool = all {

// ...

all {

msgs_signed_commit != Set(),

nondet signed_vote = oneOf(msgs_signed_commit)

on_commit(id, signed_vote),

},

// ...

}

Even though this approach to storing messages may seem to be too far off from the actual implementation, this is actually a standard pattern of specifying sent messages in fault-tolerant protocols. For instance, this pattern is used in the TLA+ specifications of Paxos, Raft, and Tendermint.

Faults. Since ChonkyBFT should tolerate Byzantine faults, we had to capture the effects of Byzantine replicas in our specification. It’s often said that Byzantine replicas may exhibit arbitrary behavior. Formal specification languages force us to specify what “arbitrary” actually means. More precisely, we have Authenticated Byzantine faults, which are defined by [Dwork, Lynch, Stockmeyer’88] as follows:

Authenticated Byzantine: Arbitrary behavior, but messages can be signed with the name of the sending processor in such a way that this signature cannot be forged by any other processor.

We formalize a single step of the faulty replicas in the action called faulty_step. Since its code contains about 160 LOC, we only show the shortest piece that injects commit votes:

...

all {

nondet senders = FAULTY.powerset().oneOf()

nondet commit_view = VIEWS.oneOf()

nondet block_hash = ALL_BLOCKS.oneOf()

nondet block_number = VIEWS.oneOf()

val signed_commits = senders.map(s => {

vote: {

view: commit_view,

block_number: block_number,

block_hash: block_hash

},

sig: s

})

msgs_signed_commit' = msgs_signed_commit.union(signed_commits),

},

...

In the above code, an arbitrary subset of the Byzantine replicas inject their commit votes for an arbitrary view, an arbitrary block hash, and an arbitrary block number.

5. From tests to model checking and back to tests

In this section, I am going to be a bit technical. Keep reading though. The main value of this section is not in the technical details, but in the differences between the different approaches to experimenting with the specification.

It is hard to write a complete formal specification from scratch, even if you have an informal specification at the input. This is why I typically write specifications incrementally:

-

Write the first specification of a simple state machine that captures only a small but useful part of the distributed protocol. For example, the state machine may only be able to send proposals, and there are no faults.

-

Run the Quint simulator via

quint runand see whether the produced examples make sense. -

Add basic tests for the core definitions and run them via

quint test. -

Write a few more actions, e.g., receiving the proposals.

-

Add “falsy” invariants, that is, state invariants that are expected to be broken. These invariants allow us to see that our specification is not over-constrained. In other words, it is doing something useful. Check them with the simulator via

quint run. -

When the tests become too hard to write, and the sample executions do not help us to see anything new, it is time to write state invariants and check them via

quint verify, which, in turn, calls the Apalache model checker. -

At this point, many obvious invariants fail. This is why it is very important to write as many of them as possible. It often happens that the informal specification has trivial bugs, which would also be caught in the implementation phase. It also happens that our state invariants are actually wrong. This is the point when the model checker helps us a lot.

-

Enable faults in the specification and see how many state invariants become broken again.

We basically followed the above methodology. Steps 1-5 look very similar to normal software development practices and thus are often brushed off by experts in formal methods. This is a grave mistake! These steps help the engineers to build confidence in the formal specification. They stop seeing the formal specification as an alien artifact and start seeing the value of having specification code that just works at a different level of abstraction.

Writing tests. We wrote a small number of test scenarios. For instance, replicas_normal_case_Test demonstrates a happy-path execution. In this test, the correct replicas are committing three blocks. If you look at the code of the test, you will notice that the test does not require any boilerplate, which is common to see in the testing frameworks for distributed systems. The reason is very simple: At this level of abstraction no boilerplate is needed! There are no services to start and stop, no need to set up network interfaces, etc. Actually, the test looks very much like an execution scenario that a researcher or an engineer would write on a whiteboard.

What I like about Quint is that it naturally integrates the testing framework and the interactive exploration. We can interactively repeat the steps of the above test and inspect the intermediate states in REPL:

$ quint -r tests_n6f1b1.qnt::tests

Quint REPL 0.21.0

Type ".exit" to exit, or ".help" for more information

>>> init_view_1_with_leader(Map(0 -> "n0", 1 -> "n0", 2 -> "n1", 3 -> "n2", 4 -> "n3"))

true

>>> all {

... proposer_step("n0", "val_b0"),

... unchanged_leader_replica,

... }

...

true

>>> all_replicas_get_propose("val_b0", 0, "n0", Timeout(init_timeout_qc))

true

>>> replica_state.keys().mapBy(id => replica_state.get(id).phase)

Map("n0" -> PhaseCommit, "n1" -> PhaseCommit, "n2" -> PhaseCommit, "n3" -> PhaseCommit, "n4" -> PhaseCommit)

>>> replica_state.keys().mapBy(id => replica_state.get(id).view)

Map("n0" -> 1, "n1" -> 1, "n2" -> 1, "n3" -> 1, "n4" -> 1)

>>>

Checking falsy invariants. It is very easy to write a specification that gets stuck somewhere in the middle. To avoid this, I usually write “falsy” state invariants, which are meant to be violated. A violation would actually give us an interesting execution that leads to the state we are looking for. For example:

// check this invariant to see an example of reaching PhaseCommit

val phase_commit_example = {

CORRECT.forall(id => replica_state.get(id).phase != PhaseCommit)

}

// check this invariant to see an example of having a timeout quorum:

val timeout_qc_example = {

msgs_signed_timeout.map(m => (m.sig, m.vote.view))

.size() < QUORUM_WEIGHT

}

Many of these invariants are simple enough so that the randomized simulator finds counterexamples to them almost instantly:

$ quint run --invariant=phase_commit_example experiments/n6f1b1.qnt

...

n6f1b1::replica::replica_state:

Map(

"n0" ->

{

high_vote: Some({ block_hash: "val_b1", block_number: 0, view: 1 }),

phase: PhaseCommit,

view: 1,

[...]

},

[...]

[violation] Found an issue (1669ms).

The simulator helps us in finding basic executions that violate falsy invariants. Once we are done writing simple falsy invariants, we write something more exciting. For example, how about producing an execution, where at least one replica commits a block:

// check this invariant to see an example of having a finalized block:

val one_block_example = CORRECT.forall(id => {

not(replica_state.get(id).committed_blocks.length() > 0)

})

This looks like a nice invariant to get a counterexample to. Let’s try that:

$ quint run --max-samples=10000 --invariant=one_block_example experiments/n6f1b1.qnt

[...]

[ok] No violation found (584447ms).

Now what? Is our consensus protocol broken and it does not let us commit even a single block? Luckily, we know that this is not true, as we have written the test replicas_normal_case_Test earlier. Moreover, we have seen the example in Figure 2. Phew.

We can throw more computing power. Since the Quint simulator is randomized, it is trivial to run multiple instances of the simulator in parallel. All we need is GNU parallel:

$ seq 0 31 | parallel quint run --seed=`date '+%s'`{#} --out={#}.out \

--max-samples=33000 --invariant=one_block_example experiments/n6f1b1.qnt

The above command runs 32 instances of quint run. We have to make sure that

these instances use different randomized seeds. Hence, we use the current date

concatenated with the instance number as a seed. Since we ask every instance to

execute 33k random runs, all instances simulate about 1 million runs together.

After running for two hours on a beefy machine, the simulator could not find an execution, where one block was committed. Read further to see how it could be faster with the model checker.

So far, we have been using more-or-less standard testing techniques that fit under the umbrella of (stateful) property-based testing, e.g., see stateful PBT in Hypothesis.

Model checking. Another way to quickly find a counterexample to

one_block_example is by running the Apalache model checker with quint

verify:

$ quint verify --invariant=one_block_example experiments/n6f1b1.qnt

[...]

[violation] Found an issue (1766648ms).

error: found a counterexample

It took the model checker about 30 minutes to find an example. Was it a bit slow? Well, if we compare it with the randomized simulator, which could not even find an example, it is not as slow.

Actually, we can find an example even faster, if we do not care about producing the shortest example. To this end, we use randomized symbolic execution and extend the maximal number of steps to 30:

$ quint verify --random-transitions=true --max-steps=30 \

--invariant=one_block_example experiments/n6f1b1.qnt

[...]

[violation] Found an issue (229946ms).

error: found a counterexample

So far, we have been using the simulator and the model checker to find invariant violations, when the invariants do not hold true. But what if the invariants do hold true? We discuss this in the section below.

6. Making the specification slower

As we were progressing with the specification, we were adding more actions and conditions to it. As a result, the model checking times were increasing. This is not surprising, as Quint translates the specification to TLA+ and runs Apalache under the hood. For such a rich specification such as the specification of ChonkyBFT, Apalache generates hundreds of megabytes of SMT constraints, which have to be discharged by the constraint solver called Z3.

At some point, we were not able to produce a counterexample to agreement for the case of 4 correct replicas and 2 faulty replicas ($n=6,f=1,b=2$), even though we knew that agreement should be violated in that case. Randomized symbolic simulation was running for hours on 20 CPU cores, but every individual step of it was so slow that we could not make much progress. We have found several ways to fix this issue, see the following sections. Certainly, the best way was the protocol optimization that was introduced by the Consensus team.

Under these circumstances, the easiest workaround is to get back to writing tests. To make sure that the specification was still violating agreement in the case of $n=6,f=1,b=2$, we wrote the test disagreement_Test. This test demonstrated that, indeed, two faulty replicas could drive two honest replicas into committing two different blocks for the same block number.

Of course, writing a test requires a very good understanding of the protocol and some creativity. In particular, we had to find the right message payloads for the test to work. Fortunately, this is where the model checker can help us in saving the efforts, too.

7. Twins

Once our specification was way too complex for the model checker — we fixed it later — we were looking into ways to analyze deeper properties without waiting for days.

The first technique we looked at was the Twins technique, which was originally applied to the consensus implementations. We are probably the first ones who applied it to consensus specifications. Since it was shown to be successful in testing actual implementations, we expected it to work well with the Quint simulator as well. Without going into details about the twins, the core idea is to let several replicas (the twins) run the correct code but give them the same private key. Hence, the replicas that have the same private key may vote differently in the same view, and this behavior will be perceived externally as equivocation by a single replica, since the other replica would not be able to distinguish between the twins.

It was relatively easy to introduce twins in our specification. In addition to replica identities, we have also introduced a mapping from their identities to the keys. For example, here is how we did it for $n = 6$ in twins_n6f1b1.qnt:

module twins {

// A specification instance for n=6, f=1 (threshold),

// 5 correct replicas, and 1 faulty replicas equivocating

import replica(

CORRECT = Set("n0", "n1", "n2", "n3", "n4", "n5_1", "n5_2"),

REPLICA_KEYS = Map("n0"->"n0", "n1"->"n1", "n2"->"n2",

"n3"->"n3", "n4" -> "n4", "n5_1"->"n5", "n5_2"->"n5"),

...)

...

}

In the above specification instance, instead of having one honest replica

"n5", we had two honest replicas "n5_1" and "n5_2" that shared the same

key "n5". The key idea is that this behavior of two replicas "n5_1" and

"n5_2" is significantly simpler than Byzantine behavior in general. Our

expectation was that it would improve the performance of the Quint simulator,

since its execution space is much more constrained in comparison to the general

case.

It was easy to introduce the Twins technique. Unfortunately, it did not

help us in uncovering new behavior. For example, we could not find a

counterexample to agreement_inv for the case of four honest replicas and two

pairs of twins, which is specified in twins_n6f1b2.qnt.

8. Guided model checking

This section goes a bit into the guts of the Apalache model checker. If you find it too technical, just skip it.

Why does the model checker slow down? There are multiple reasons. The two most obvious reasons are the following:

-

A large number of constraints are produced by the model checker, e.g., due to a high degree of scheduling non-determinism.

-

The protocol has a large number of potentially reachable states.

We will see what we can do about the reason (2) in the next section. In this section, we will see what could be done about (1).

What is a high degree of scheduling non-determinism? As is common in formal modeling of distributed systems, an execution of a distributed system is understood as a sequence of steps by individual replicas. In other words, we consider all sequences of transitions made by replicas under all possible interleavings (schedules). Since we specify potential transitions via actions, we will talk about all possible interleavings of actions.

Let us have a look at the choices of transitions in the four steps of our specification, starting from an initial state:

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

proposer_step |

proposer_step |

proposer_step |

proposer_step |

on_new_view |

on_new_view |

on_new_view |

on_new_view |

on_timer_is_finished |

on_timer_is_finished |

on_timer_is_finished |

on_timer_is_finished |

faulty_step |

faulty_step |

faulty_step |

faulty_step |

on_proposal_step |

on_proposal_step |

on_proposal_step |

Let us have a closer look at the above table. In an initial state of the

protocol, we are in view 1. As expected, the view proposer may propose a block

by executing proposer_step. In addition to that, an honest replica may receive a

NewView message from view 0 — for a technical reason, the protocol is

bootstrapped by all honest replicas issuing timeouts in view 0. Also, an honest

replica may timeout. In addition to that, the faulty replicas can make a step.

All schedules. Now, I will tell you the secret about how the bounded model checker in Apalache works. For the executions of up to 4 transitions, it produces SMT constraints for all the actions in the above table. Then it adds an assumption that only one of the actions may take place in every step. This adds constraints for 19 potential steps. What is more important for understanding the slowdown is that the solver has to consider all possible choices of the 19 actions in four steps. If you were solving systems of linear inequalities at school, you can imagine how the solver would have to combine different cases.

Random schedules. Analyzing all executions at once seems to be wasteful. What if we could analyze only one interleaving at a time? Without going into definitions, this is what is usually called symbolic execution. Since in our protocol many actions are enabled simultaneously, this would produce $4 \cdot 53 = 600$ interleavings and symbolic executions for just 4 steps! For this reason, Apalache implements randomized symbolic execution. That is, an interleaving is chosen at random, and a sequence of steps is encoded as symbolic constraints for the given interleaving. By default, Apalache enumerates 100 such executions. In practice, many interleavings are somewhat similar, they lead to the same states. As a result, 100 random interleavings find bugs as good as enumerating 600 interleavings. If you are curious, there is a whole theory of eliminating unnecessary interleavings, called partial-order reduction. Apalache does not implement it though, falling back to randomization.

Guiding schedule selection. Now, enumerating all schedules is hard. Checking

them at random is easier, but there is a probability of missing an interesting

state. The model checker is completely unbiased towards any actions. For

example, it does prefer on_proposal_step over on_timer_is_finished. This is

also the power of the model checker, as it comes up with counter-intuitive

executions.

What if we do not want to start from an arbitrary initial state? Say, if we want to find an example of two blocks being committed, we know that at least one of them should be committed first. Hence, we could drive the protocol into a state, where one block has been committed, and continue the search from there. This is an example of guided model checking.

To our luck, we do not have to extend Apalache to get this behavior. The logic of TLA+ behind Quint is so powerful that we can easily specify such a scheduler in the language itself. To this end, we extend replica.qnt in guided_replica.qnt. We have to introduce a bit of boilerplate code, due to the current limitations of Quint, more on that later. The important declarations are given below:

// the input trace to restrict the model checker's search space

const G_INPUT_TRACE: List[StepKind]

...

// remaining steps to replay

var to_replay: List[StepKind]

The trick is that we define a list of steps to replay. With every step, we consume the head of to_replay and restrict the step, as prescribed by the head:

// initialize the replicas together with the trace to replay

action g_init: bool = all {

init,

to_replay' = G_INPUT_TRACE,

}

// execute the same actions as in replica::step,

// but restrict their choice with to_replay

action g_step = {

any {

// nothing to replay

all {

length(to_replay) == 0 or to_replay[0] == AnyStep,

to_replay' = if (length(to_replay) == 0) to_replay else tail(to_replay),

step,

},

// steps to replay

all {

length(to_replay) > 0,

to_replay' = tail(to_replay),

val expected_step = head(to_replay)

any {

all {

expected_step == FaultyStep,

faulty_step,

unchanged_replica,

leader' = leader,

},

...

}

Once we have done that, we can introduce a specialized version of the

specification that guides the scheduler according to G_INPUT_TRACE. Once the

schedule has been exhausted, the model checker starts its unrestricted

exploration, as in the general case.

For example, here is how we can initialize G_INPUT_TRACE to make all honest

replicas commit one block:

G_INPUT_TRACE = [

ProposerStep("n1"),

OnProposalStep("n0"), OnProposalStep("n1"), OnProposalStep("n3"),

OnProposalStep("n4"),

FaultyStep,

OnNewViewStep({ id: "n0", view: 2 }), OnNewViewStep({ id: "n1", view: 2 }),

OnNewViewStep({ id: "n2", view: 2 }), OnNewViewStep({ id: "n3", view: 2 }),

OnNewViewStep({ id: "n4", view: 2 }),

]

Importantly, we do not specify the gory details in this execution, e.g., which

messages are to be sent and received. Instead, we specify only the kinds of

steps and replica identities. In the case of OnNewViewStep, it’s also crucial to

submit the view. It’s the job of the constraint solver to fill in the gaps.

We used this approach to find an example of an honest replica committing two

blocks. It takes bounded model checker — verifying all interleavings

— a bit less than two hours to find an example of

two_chained_blocks_example:

$ quint verify --max-steps=50 --init=g_init --step=g_step \

--invariant=g_two_chained_blocks_example n6f1b1_quided_one_block.qnt

...

[violation] Found an issue (5984680ms).

It takes just about five minutes to find an example with randomized symbolic execution (since we are using randomization, the running times may significantly vary):

$ quint verify --max-steps=30 --random-transitions=true \

--init=g_init --step=g_step \

--invariant=g_two_chained_blocks_example n6f1b1_quided_one_block.qnt

...

[violation] Found an issue (378368ms).

In our actual experiments, we were actually running randomized symbolic execution in parallel on 16-32 CPU cores. This lets us produce examples even faster.

9. Making the specification faster

At some point, we made an estimate of the potential state space. We considered the following protocol configuration:

- Six replicas, one of them faulty.

- Up to 4 views.

- Up to 2 valid blocks and 1 invalid block.

This configuration is probably the minimally interesting one. Yet, when we made the estimate of how many different messages could be sent by the Byzantine replica, the figure was really staggering:

When I started doing some preliminary work on finding an inductive invariant, this figure became quite important. For inductive reasoning, we have to start in a more or less arbitrary state. It became clear that one particular message type could potentially carry plenty of data, especially if it was produced by a Byzantine replica. This was due to the fact that a timeout quorum certificate carried the votes of individual replicas, each of them being able to additionally carry a commit quorum certificate.

During our meeting, the Consensus team immediately found a solution that would dramatically reduce the size of timeout quorum certificates. As we have specified this idea, model checking times were significantly reduced.

10. Model checking invariants that hold true

As we were writing the protocol specification in Quint, we were also formulating

state invariants. Such invariants were instrumental in catching typos and

missing validation tests in the protocol. One thing about auxiliary state

invariants that is rarely understood: Even though we could find some of the bugs

by checking safety properties such as agreement_inv, having a richer set of

state invariants helped us to detect the same bugs with the model checker much

faster.

The latest version of the protocol specification has 18 state invariants. Some

of them are relatively easy to understand. For example,

no_proposal_equivocation_inv checks that honest replicas do not cast different

proposals in the same view:

// a correct proposer should not equivocate for the same view

val no_proposal_equivocation_inv = tuples(msgs_proposal, msgs_proposal).forall(((m1, m2)) => or {

not(m1.justification.view() == m2.justification.view() and m1.sig == m2.sig),

FAULTY.exists(id => sig_of_id(id) == m1.sig),

m1.block == m2.block,

})

Some invariants capture a deep understanding of the protocol. For example, one_high_vote_in_timeout_qc_inv states that it should not be possible to extract two high votes from a timeout quorum certificate.

We have also found these state invariants to be quite helpful in quickly detecting issues that were introduced during protocol refactoring. For example, the model checker produced an example that was exploiting a missing verification of a commit quorum certificate. This issue was quickly fixed in the Quint specification and the informal specification.

We have checked the invariants in several configurations:

-

Case $n = 6, f = 1, b = 0$: Six replicas, all of them honest.

-

Case $n = 6, f = 1, b = 1$: Six replicas, one of them Byzantine.

-

Case $n = 6, f = 1, b = 2$: Six replicas, two of them Byzantine. Many invariants are violated in this case.

-

Case $n = 7, f = 1, b = 1$: Seven replicas, one of them Byzantine.

Since enumerating all interleavings takes too much time for ChonkyBFT, we checked the invariants against 100 instances of symbolic execution of lengths up to 25 steps. Since we ran the experiments multiple times, the actual number of tried interleavings is well beyond 100.

11. The goodies and rough edges of Quint

On the positive, I find Quint tooling to be quite adequate for writing and analyzing formal specifications of distributed systems. Obviously, I am biased, since I have designed and developed large parts of Quint and Apalache. Here are a few highlights of Quint tooling that I have found to be extremely useful in this project:

-

Refactoring. Quint really shines at refactoring. Whenever the protocol was changed, the type checker was reporting inconsistencies in multiple places. While it was annoying to fix all these type errors one-by-one, it would be much harder to spot them in an untyped specification language such as TLA+.

-

Types. All mainstream programming languages use types. Hence, engineers expect them, too. By defining types of the core data structures, we could ignite the discussions about the protocol specification.

-

Tests. Unit tests and property-based tests are commonly used by software engineers. In contrast to TLA+, Quint offers specification writers a unit-testing framework. By leveraging non-determinism in Quint, specification writers effortlessly extend unit tests to property-based tests. Importantly, tests offer us a fallback option, when the model checker and the randomized simulator are too slow.

Now that I have praised Quint, I should be honest and mention a few issues with the tooling:

-

The module support still has issues. For instance, when we had to define an instance for guided model checking in guided_replica.qnt, we had to introduce boilerplate definitions to cope with the Quint parser.

-

The type errors reported by the type checker are not useful. It’s easier to just ignore them and massage the types, instead of reading the messages.

-

Some recent language features break in unexpected places, e.g., I ran into issues when using a user-defined version of the option type, see #1451.

-

Temporal operators are kind of supported, but there is not much documentation.

In addition to that, we have felt lack of the following features:

-

It would be great, if the testing framework could verify the state invariants in the intermediate states of the tests it is running. Since the tests are already giving us non-trivial and important executions, we are missing an opportunity there. We were manually adding such assertions in the tests, but these assertions were distracting us from the core of the tests.

-

As we were discussing in the section on guided model checking, we extended the specification to drive the protocol into states of interest. While the model checker reaches those states faster in the guided specification, it still takes some time to do it. It would be great, if the model checker could save such intermediate contexts, and reuse them later.

-

If Quint supported some syntax for guided search, it would make our job significantly easier.

In any case, there are no serious issues that could not be fixed by a dedicated tooling team in six months.

12. Conclusions

I believe that we have brought great value to the project with our efforts in formal specification and model checking with Quint and Apalache. We have already summarized the benefits of using a specification language (Quint) and a model checker (Apalache) in the introduction.

One issue with informal specifications is that they are open to interpretation. Even if they look very much like code, different readers may understand various pseudocode primitives differently. A specification language uses a fixed logic interpretation that eliminates ambiguity. While a programming language also fixes an interpretation – concurrency and non-determinism aside – specification languages are much more concise than programming languages. This is especially true for languages like Quint and TLA+, since execution efficiency is not a concern. For instance, see my blogpost about memory in specifications.

In my experience, the real killer feature of our approach to specification is the ability to quickly produce examples and counterexamples with the tools. This helps all parties to get better confidence in the protocol. As there is no single magic tool that is able to do that in all cases, we are using a portfolio of tools and approaches: The randomized simulator, unit and property-based tests, the bounded model checker, randomized symbolic execution, and guided model checking.

As we have mentioned before, doing an exhaustive model checking of ChonkyBFT is quite challenging, due to its rich behavior and the size of the potential state space. Thus, we have mostly used randomized symbolic execution.While this technique is surprisingly efficient at finding counterexamples, it is inherently incomplete, that is, there is still a chance of violating some of the invariants. Hence, we are investigating inductive reasoning for ChonkyBFT. Stay tuned to read about our future results.

It is worth noting that analyzing consensus protocols is challenging in general, and ChonkyBFT is no exception here. For example, see Formal Verification of HotStuff by Leander Jehl (2021) and the PhD Thesis by Diego Ongaro on Raft (2014), which both applied state enumeration with TLC. Byzantine faults add another dimension to the problem, as Byzantine replicas produce incredibly large state spaces. In this case, symbolic model checkers such as Apalache have a better chance of succeeding, as exemplified by our earlier verification results for Tendermint Accountability (2019-2020).

Do you want to receive notifications when I write something new? Subscribe to the newsletter. New blog posts are going to be announced once per week (maybe twice, if I really have something!).

If you want to pick up my brain for a few hours, drop me an email. After that, we can switch to a messenger of your choice (e.g., Signal, Telegram, or others) or have a call. For short consultations, I accept payments via Stripe. I also consider longer-term engagements (from weeks to months), which would require a contract. You can see my portfolio at konnov.phd. I am based in Austria (CET/CEST) and have experience working with clients from the US, UK, and EU.

The comments below are powered by GitHub discussions via Giscus. To leave a comment, either authorize Giscus, or leave a comment in the GitHub discussions directly.